The Greatest Plot Twist of All...

Our dueling human nature, Charles Dickens, and the genius of Scrooge

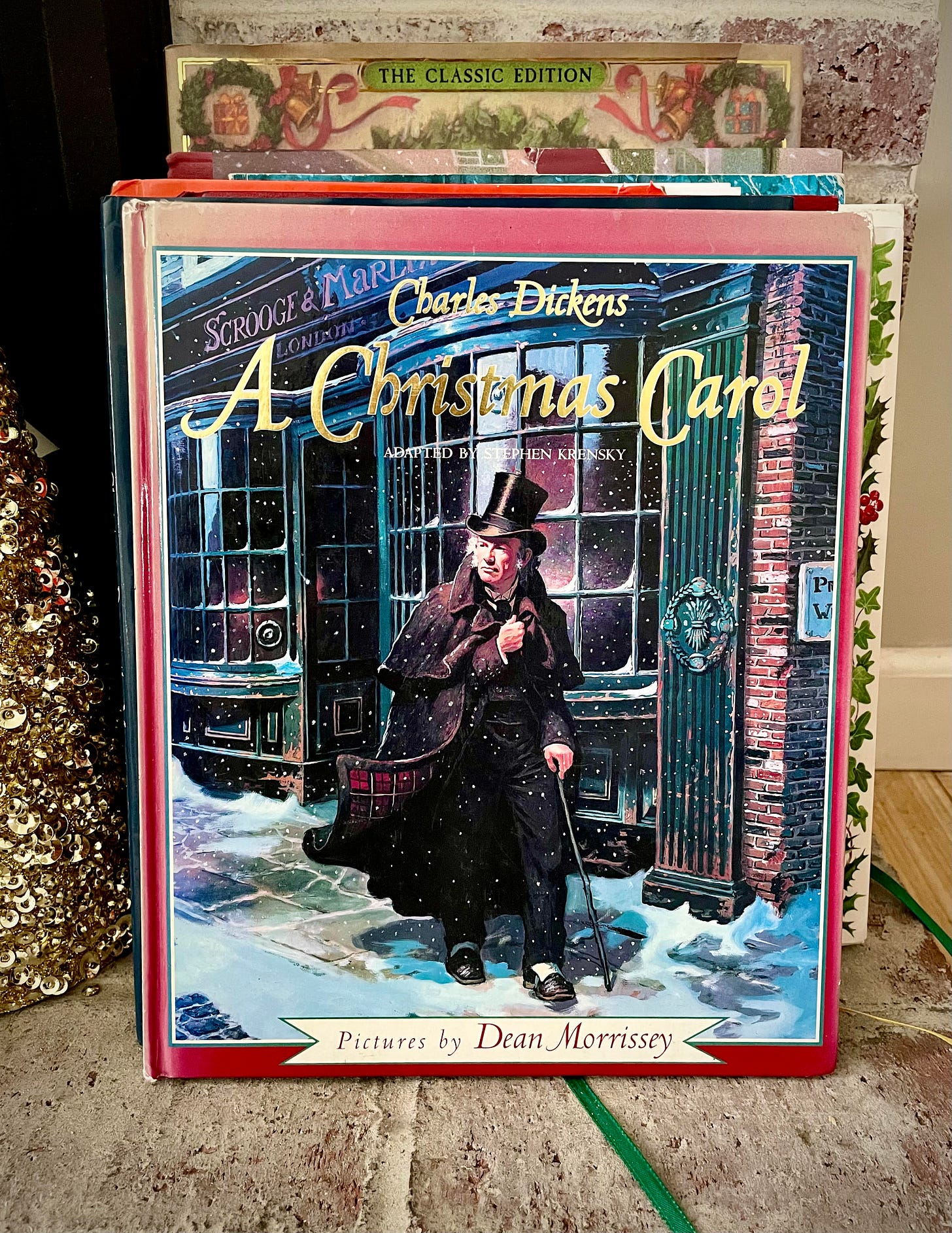

The year was 1843, and a 31-year-old writer named Charles Dickens was not only in need of money (his latest novel had been a flop), but he was greatly distressed about the child labor problem across the United Kingdom.

Dickens was well familiar with the crushing labor forced upon children. As an 11-year-old working in a factory assembly line, he was one of many unskilled cogs hammering the same nail or gluing another piece of something hour after hour, day after day to pay off his own father’s debt.

He did get to school, and later worked as a clerk, journalist, short story writer, and novelist. Oliver Twist was published in monthly installments from 1837-39.

At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for young girls to be sewing dresses for “16 hours a day, six days a week, rooming-like Martha Cratchit-above the factory floor” or for 8-year-old children to work 11-hour days dragging coal carts through tiny “subterranean passages.”

The population of England had ballooned, with workers leaving the countryside for the manufacturing companies in the cities. The value of an unskilled laborer was measured by the ha-penny, or how many nails one could hammer in an hour.

The 1840s in England became known as “The Hungry ‘40s,” with the poor taking whatever work they could get. “And who worked for the lowest wages? Children.” Death came early for many.

In the spring of 1843, Dickens wandered the streets of London as he prepared a pamphlet he thought of calling, “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.”

In less than a week, he had worked out a more effective delivery for his message: a story.

I like to think of his mind brewing with all of the details and plot points and characters all of that summer and into fall until the ghost of Marley, Tiny Tim, and Ebeneezer Scrooge were born. When Dickens began to write, he finished A Christmas Carol in less than six weeks, his characters now fully formed.

That story, they say, wasn’t what the people were asking for - it was the story they needed.

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,' faltered Scrooge, who now began to apply this to himself.

Business!' cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. "Mankind was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The deals of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

― Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

For writers, what Dickens did is immensely inspiring (and something I mention quite a lot): our own true-life experiences can lead to powerful and beloved fiction.

Fiction can also be a damning report, a powerful record and/or motivator of societal change.

Though the old language makes it hard to read today (I’m guessing we mostly tell the story orally or watch it on the screen or play), A Christmas Carol is as popular now as it was one hundred and eighty three years ago in 1843. For many, it ushers in Christmas as much as the nativity does. We know what Scrooge needs, that miserable miser, because his human nature is also ours.

And the answer for so much that ails our human nature might still best be told with a story.

“You are fettered," said Scrooge, trembling. "Tell me why?"

"I wear the chain I forged in life," replied the Ghost. "I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.”

― Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

And, hey, who doesn’t feel like Scrooge some of the time?

'If I had my way, every idiot who goes around with Merry Christmas on his lips, would be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart. Merry Christmas? Bah humbug!'

Bah humbug. Go ahead. Feel it. I won’t begrudge you.

Just don’t stay there. Because we Scrooges must evolve and put down the chains we forged or there is no story, no happy ending.

Thankfully, Scrooge has his ghosts reminding and warning him to get out of his own way. And finally he does - a turkey for Tiny Tim (medical care and fair pay for his employees, including holiday paid leave)!

(fun fact: Tiny Tim was based off of Dickens’ nephew).

The ultimate plot twist is one of irony: it is only in the doing for others that Scrooge finds joy.

It models what Christianity and every major religion teaches, another great irony: we find ourselves only in the losing of self.

This realization delights readers because we love a great plot twist. Especially one that’s counterintuitive to our selfish natures, but resonates so completely as truth.

Scrooge is the representative of everything good or “not great” with how we talk about “self-care” these days, and I wonder - how much are we really caring for self if it doesn’t leave room for caring for others?

We live in a fallen world, a selfish one, a world at war, with epidemics of sadness, depression, and loneliness. We spend a lot of time on self. Even our literature is extremely self-centered (see Jennifer’s excellent piece here). Literature can serve many purposes. Not everything needs to move us profoundly, but our favorite stories will. In those stories there are answers to the plagues of our time. Like this one: Love always wins. Every single time.

Chills.

“And it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One!”

― Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

I think yes, A Christmas Carol was better than a pamphlet.

To the keepers of Christmas…

Amy <3

p.s. Some of my other favorite Christmas stories include Christmas Day in the Morning by Pearl Buck, The Legend of the Poinsetta by Tomie dePaola, The Best Christmas Pageant Ever by Barbara Robinson, and The Gift of the Magi by O Henry (remember when Della cut off her beautiful hair?!)

_

Notes:

https://time.com/4597964/history-charles-dickens-christmas-carol/

https://www.arts.gov/stories/blog/2020/ten-things-know-about-charles-dickens-christmas-carol#:~:text=Like%20many%20of%20Dickens'%20other,and%20work%20at%20a%20factory.

https://www.writerstheatre.org/charles-dickens-biography

https://www.goodreads.com/work/quotes/3097440-a-christmas-carol

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/02/1173418268/loneliness-connection-mental-health-dementia-surgeon-general

Good News and Fun Stuff…

ICYMI: I have a few books left - mostly paperback! Thanks everyone, for getting in touch! Such JOY to sign and put books in the mail for you…

WRAD: World Read Aloud is on Feb 7. I have some afternoon spots. Get in touch if you want me to zoom into your classroom!

LIGHT THE WORLD: Make December “acts of service” a fun game with your classroom or family: see how many “kind things” you can do together or individually. Report back at the end of the day. Christmas cookies, caroling, taking out the trash, writing a letter to grandma, forgiving a friend, a turkey for Tiny Tim. SO MUCH LIGHT, SO MUCH JOY. Less Scroogey.

Hi Amy, I saw that you are on Writers at Work and read your post. I wanted to join your Substack because you wrote about A Christmas Carol, my fav. Thanks!

Very nice, Amy. Yes, stories are fundamental to how we understand the world and ourselves. They are vehicles of communication that depend upon our connections to others, and give the lie to the misconception that person-hood depends only on the individual self. The truth is that our first awareness is of other persons, of the warmth of a maternal breast, the wide-eyed face of a parent cooing encouragement to recognition and connection - we know the other before the self. It saddens me when others brag of reading only non-fiction, since they are cutting themselves off from what has always been a precious fount of imagination, the mysterious what-if that deepens our understanding of ourselves and others. Even in the sciences, the proof of a theorem or the marshaling of empirical evidence provides a thrill that goes far beyond the dry Q.E.D. - the trains of thought, the perceptions of connections among concepts, were originally denizens among others of the "fictional" wood of the unknown, and following the paths that led to them in that wood is another kind of "story" that our species seems to crave as part of making sense of ourselves.

Enough blather - thank you, Amy.

-Greg Johnson